Medieval Medicine

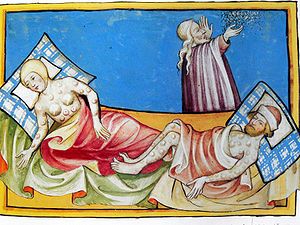

The Middle Ages are often seen as a shadowy period of limited medical knowledge and great superstition. But many ideas from the classical medicine of the ancient Greeks and Romans survived into the medieval period relatively intact. Medical knowledge also arrived in Europe from the Arab world over the centuries, and doctors were familiar with the medicinal properties of some plants. However, treatments and cures were often as much to do with magic and superstition as they were associated with real medicine.

Doctors were very much guided by astrology in the Middle Ages. The Church, which influenced so much of medieval life, strongly disapproved of astrology, but found it difficult to stamp out. During the worst period of the Black Death, astrological charts became even more important for doctors. As the illness reached a noticeable crisis point, after which a patient either recovered or died, the time of recovery and the position of the stars and planets were seen as very significant. Even Guy de Chauliac, physician to three popes in succession, and author of the leading work on medieval surgery, was a firm believer in astrology. For operations, he would use recognized anesthetic potions, but also recommended bleeding and other procedures based on the position of the planets. Illnesses were also determined to be serious or not depending on whether they were under the sun’s or the moon’s influence.

As far as medicines were concerned, many medieval concoctions were little more than witch’s brews. One of the best-known medicinal drugs of the Middle Ages was treacle or theriac, a blend of sixty-four different drugs in honey. Sold as a cure all, it was claimed to heal fevers, prevent internal swellings, clear skin blemishes, help with heart trouble, dropsy, epilepsy, and palsy, assist with sleep, aid digestion, strengthen limbs, heal wounds, and of course, cure the plague. Doctors at the time did make use of herbal remedies too. However, here again astrology had a distinct influence. The genuine medical properties of some plants were also related to how, and by whom, they were collected. Betony had to be picked by a small child in August before sunrise, and marigold when the moon had entered the house of Virgo. A herbalist also had to recite the proper designated prayers when preparing the medicine.

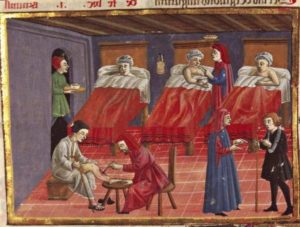

And yet, medieval doctors were also skilled at a variety of medical procedures. They could set broken bones, extract teeth, take out bladder stones, remove cataracts, and restored a scarred face by skin grafts from the arm. They knew that apoplexy and epilepsy were related to the brain. Urine samples, feces, and pulse rates were used to analyze ailments, and doctors were aware of which substances were diuretics and laxatives. It was also firmly believed that prevention was better than cure and great emphasis was placed on a healthy lifestyle, in which diet, exercise, mental attitude, and reduced stress all played a part.

Surgery was practiced in the Middle Ages too, although it was seen as a last resort. It is known to have been successful in the treatment of breast cancer, gangrene, hemorrhoids, and other conditions. There are illustrations showing medieval surgery, but naturally they give no indication of the pain suffered by the person on the operating table.

Anesthetics were used, but many of the concoctions used to relieve pain or induce sleep were also potentially fatal. Dwale, for example, consisted of gall from a cow or castrated boar, lettuce, briony, opium, henbane, and hemlock juice mixed with wine. The opium, alcohol, and hemlock would have made the patient incapable. Henbane and briony would have quickened the passage of poisons out of the body. However, it must be noted that hemlock was particularly dangerous, with too much being a death sentence.

Anesthetics were used, but many of the concoctions used to relieve pain or induce sleep were also potentially fatal. Dwale, for example, consisted of gall from a cow or castrated boar, lettuce, briony, opium, henbane, and hemlock juice mixed with wine. The opium, alcohol, and hemlock would have made the patient incapable. Henbane and briony would have quickened the passage of poisons out of the body. However, it must be noted that hemlock was particularly dangerous, with too much being a death sentence.

Despite their skills and knowledge, for diseases and ailments beyond their abilities doctors fell back on solutions that seem bizarre to the modern reader. Ringworm was treated by washing the patient’s hair in a boy’s urine. Gout could be relieved by a plaster of goat dung mixed with rosemary and honey. Bloodletting was also popular as a cure for just about everything, with many different parts of the body used. For example, the two veins in the neck were to be tapped for leprosy, while the basilic vein, just below the elbow was said to clear the liver and spleen of any impurities.

If everything failed, charms, sacred relics, and incantations were used to ease the pain of childbirth, help contraception, cure toothache, remove boils, and even mend broken arms and legs. Medical knowledge eventually improved, but not immediately and for centuries to come, doctors were still very much influenced by superstition in the performance of their duties.